Christopher Elizabeth(they/them) is a Black-Indigenous jack-of-all trades storyteller, who enjoys the process of creation, whether that be music, writing, or all the inner workings of a theatre. They have worked as an actor and stage manager for various non-profit companies in Southern Ontario. Elizabeth is developing their playwriting, design and video editing skills at the University of Windsor’s School of the Dramatic Arts. Elizabeth is grateful to be a part of DSF’s Digital Internship program, and is ecstatic that The Reaper & The Whale is debuting as part of DSF’s digital season.

This is a 15 min interview with Christopher Elizabeth, the playwright of the original online production the Reaper and the Whale. The interview is planned and carried out by two of our R&W production team members, Dylan Gottlieb and Fan Yi. This blog post is prepared by Alice Yang.

FULL TEXT TRANSCRIPTION

Dylan: Hi, I’m I’m Dylan Gottlieb, I use he/him pronouns, calling in from the East Village in New York, New York, and part of the Davis Shakespeare Festival internship and on the marketing team of “The Reaper and the Whale.”

Chris: My name is Christopher Elizabeth, I go by they/them. I am at the University of Windsor in Coquille, Canada, and I’m also one of the digital interns for the Davis Shakespeare Festival. I am also the playwright of “the Reaper and the Whale,” and I’m also co-directing it with two other folks.

Dylan: Could you talk a little bit about how you first got the idea to write this incredible play?

Chris: I’d like to start with talking about myself because I love doing that. I worked at a call center. It was my first, like, adult job. I hated it a lot. And at almost every lunch, I had this little notebook, it’s actually somewhere in my bookshelf, where I would just document how I felt about that day. And I’m like, “This is what sucks about working here.” And I was like, “I’m just going to work here for, like, research, because one day I’m going to write a musical about this and I’m going to dunk on this company.” I didn’t write a musical about it, actually. Believe it or not, I wrote a play, and it wasn’t just about working there. It was about working there, and I also worked like three door-to-door sales jobs. And that’s where I got my sales experience. Part of what I saw in the workplace was, like: I saw a lot of racism, a lot of sexism, and there’s a lot of micromanagement going on. And that’s the main reason I didn’t like it. It’s one of those jobs like they’re always paying attention to, like, your metrics, how long are your phone calls and like, are you like cutting? Are you giving people too much? Are you canceling people’s bills too much? All these things—the worst thing was average people time, because I love talking on the phone with people who want to talk on the phone with me. And on top of that, like. I worked in Canada out of a Canadian building, but I have what I like to call, and what has been popularized by one of my favorite movies, “Sorry to bother you,” is called a white voice. And because of that, a lot of the phone calls that I got would start off by, like, people saying like, “Oh, thank God I’m talking to an American this time,” which is just. So many things, there’s so much to unpack there. The main thing for me is the irony. A lot of my coworkers were Nigerian and Indian and they had Nigerian and Indian accents, and they always got harassed because of it. Like they’re no more or less competent than I am. Actually a lot of them were better than I am, because some of them still work there! They can put up with a lot more. And they’re amazing for that. And some of them are like master’s students. And I just can’t believe all this disrespect they got because they have an accent. Yeah. So in short, that job sucked. I worked in sales. I hated that, too, because it was just super manipulative. Yeah, so that’s that’s the inspiration.

Dylan: If you were to hypothetically describe the Reaper and the Whale in a relatively short frame, how might you?

Chris: Number one would be it’s satirical. Like, satirical in its original sense. It’s a hard criticism of capitalism, very strong. It’s taking the idea of calls to its logical evil conclusion of being like, selling death to people, basically. It’s satirical, it’s extremely sarcastic. And it’s a black comedy about the workplace and about death. And ultimately, I think it’s a tragic story despite all of this like satire. And there’s a lot of comedy in it because that’s how I cope with my problems. But ultimately, this comedy is like — it’s very tragic.

Dylan: So, both “The Reaper” and “The Whale” are individual plays— but here they’re going to be performed together. I’m just wondering if you have any thoughts about the significance of those individual works being presented together, as they will be soon

Chris: There are a few reasons. Significantly, I like that these stories stand alone. And I wrote these to be put in either order so you could watch “The Reaper” first or you could watch “The Whale” first, because it’s kind of like watching a sequel or prequel. So if you watch “The Reaper” first, then “The Whale” turns into kind of a sequel, and if you watch “The Whale” first, “The Reaper” turns into a prequel, and depending on which order you watch them in— it’s satisfying both ways, but for different reasons. And they’re both standalone narratives on their own. A lot of people who came to staged readings were surprised, actually, that that’s only act one. What else could they, like— “This seems like such a solid ending, what could be next?” So like, from a digital theater standpoint, that’s another huge reason I wrote it. There’s not a lot of digital theater work, like official digital theater work exclusively for the medium. I wanted to write something that could be performed that way. And, working on digital shows that have like multiple acts, I found out that a lot of people actually just leave halfway through. So I thought it would be— not just from a “Creative” perspective, but just from an “Audience getting a story” perspective, I thought that, like, they can— if they’re like, “OK, I’m done,” they can just go if they so please. They’ll be missing out, of course, but. They wouldn’t if they watched the full story.

Dylan: I think now might be a good time to pivot into that sort of broader discussion that you sort of mentioned earlier about the death industry and sort of raising the question of, you know, what is urgent about this work in the society that we’re currently living in?

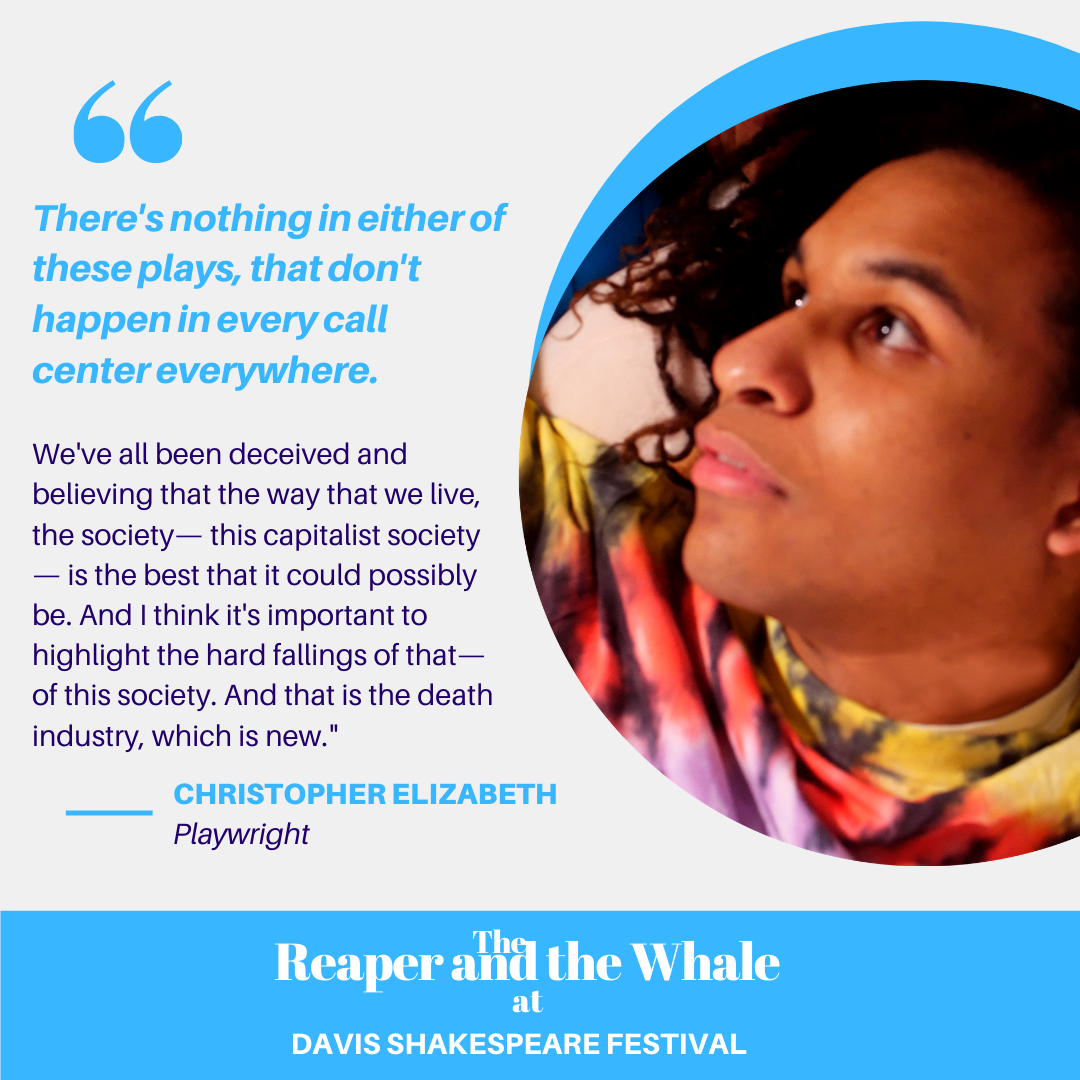

Chris: Well, first of all, we live in a society. That’s kind of the biggest thing, though, like. That— we were told at such a young age. I mean, I’m a Gen Z millennial, whatever, whichever one I decide on that day. I’m in that no-zone. But like since I was born, I was told that this is like the best it has ever been and it’s the best that it can possibly be. And working in this workplace, it doesn’t feel that way. You know, I feel like all of us have been lied to. We’ve all been deceived and believing that the way that we live, the society— this capitalist society— is the best that it could possibly be. And I think it’s important to highlight the hard fallings of that—of this society. And that is the death industry, which is new. It’s, like, been a huge inspiration for this play and learning about it, about the death industry— which was at first, by the way, the whole “Death” part was an aside in “The Whale,” when that was just its own thing. I just had a small side to it. It was a phone call. And then my dramaturg was like, “This sounds like it could just be a whole thing.” I’m, like. “Hmm.” And then it was. The fact that the death industry is the thing, the fact that a few weeks ago, this famous, Caitlin Doughty. She’s like a famous mortician, she had talked a little bit about COVID, and somebody had told her that COVID-19 was a huge business opportunity for her, for her business, for her funeral home. And that was disgusting. But that’s what we live in, and this is “The best that it gets?” So that’s kind of the “Why”— like that’s “Why now.” This is just the conversation that has been needing to happen for a very long time. And I haven’t really heard it. And that’s exactly why now. And it’s a good place to not only talk about the death industry, but also talk about like, monopolies, and these duopolies and triopolies that we have, because, there are like, especially in the Whale, this one company was inspired by a company in Canada that is part of what we call the Big Three, where they own a third of everything in Canada. But, yeah, it’s good to hit on that and kind of to get an “In” on what those practices are. And to really I think— adding these practices to the death industry, which is something that is already grotesque, will really highlight what these people actually do day-to-day. Because there’s nothing in either of these plays, that don’t happen in every call center everywhere.

Dylan: What have been the sort of influences over the course of the writing process that maybe led to changes in perspective? Do you foresee any future changes, any future drafts?

Chris: I guess the main influence has been my — just my anger. My rage. That’s always a good thing to really get me going. As you can see, all of the five music instruments behind me. I channel rage into my music, even if it sounds really chill. I don’t have a SoundCloud to plug. Don’t even— don’t get me started. Maybe one day. It’s for me. But like, the influence has been, especially listening to that, like the Caitlyn Doughty saying somebody told her that was a great business opportunity. That disgusted me. So that really inspired me to write a lot that day. And I think after hearing that, I finished the first draft in like a day or two. And what’s changing over the process is the cast. So I got to do a staged reading and something really important to me, and someone who is inspiring to me, was a Canadian playwright, and his name is Marcus Youssef. I was the stage manager for a digital play. And he— the way he wrote this play is he interviewed all the actors and came up with a story based around their identities. And one of the actors was —she’s from El Salvador, and Marcus is, I believe, Egyptian. So there are some similar experiences between those. Just being a brown person. And it was like, during the Black Lives Matter movement, like that’s when it happened ( on this play was based.) There’s the idea of tokenization. And there are some experiences between people of color that are— that we share. We share those experiences. So with the lead role of the of “The Reaper and the Whale,” for— I think for the purpose of this interview, I’ll call her by what her name is— like, what I wrote her name is, it’s Trish. And that name was off the top of my head, but also, my great great grandmother’s name is Thiwesa. That’s Oneida. I do forget what it means, but. Part of that— her name being Thiwesa is important in the play because nobody knows how to pronounce it. That’s actually why she decides to just go with Trish— it sounds similar enough. So what changed in the reading was, we didn’t have, like, an actress of color to play Trish or Thiwesa. So I wrote around that person’s identity. So this person was Portuguese, which is noticeably not a person of color, but she also gets mistaken for a person of color often just because she has darker skin. Which is why she even got cast in the first place. Because the people I was working with, we all thought that she was a person of color. So we wrote with that in mind— we changed the ending and it changed the dynamic. And we changed her name from Trish and Thiwesa to Mayara and Maya for short, just to make it more relevant to her, because that name just makes more sense. Thiwesa’s a very specific name to Oneida. Right? So in any future change, if this show gets published, it’s something that I want to make very forward, like write in a forward saying, like, “Please, if necessary, change the names of any of these actors based around their identity, because that’s really important to me.” It’s important, that, like. I don’t— because I know that some of these experiences are important. The main thing about the identity here is the mispronunciation of the name. And that that goes for anybody who has like a name that’s weird, really, but. I think it’s a really universal experience that people who don’t have, like, very American, English sounding names. Yeah, that’s something that I want to make very explicit. And that’s something that I think needs to change with every show. So essentially: names. The names need to change based on the identity of the actors. One hundred percent, and as well as the pronouns.

Music Credit: https://www.bensound.com